Home, Yaakov Israel_Gerusalemme

Mention Energheia Israel Award 2018

Jerusalem 2018

Things are not only things, they bear human traces, they continue us. The objects that accompany us for long periods of time are not less loyal, in their modest and devoted way than the animals or plants that surround us.

Lydia Flem, The Final Reminder: How I Emptied My Parents’ House, (London, Souvenir Press Ltd, 2007; My translation from Hebrew).

I wake up in the middle of the night, stunned and anguished. These are my parents. From that simple fact, everything follows. I realize that beyond the rolls of film and the few good pictures, the demands of my project and my confusion about its meaning, is the wish to take photography literally. To stop time. I want my parents to live forever.

Larry Sultan, Pictures from Home (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992) p. 18.

Who am I?

A product of my parent’s upbringing

Who are my parents?

I’m not really sure.

The first thing that comes to my mind when someone says something that makes me think of home is apartment number 26 in the last building on Brazil street, in which I grew up and in which my mother still lives today. This memory comes in fragments; The entrance to the large grey apartment block, the four flights of stairs leading down to the ground floor apartment; the peeling walls covered in old cobwebs; the once white electricity cabinet on the wall outside the old dirty brown metal front door with its square handle.

Once the door opens you find yourself in the small room that functions as a dining room. On the biggest wall is an old reproduction of Hieronymus Bosch, a diptych describing heaven earth and hell, the image is hardly visible, faded in its old crooked frame. In the middle of the room stands a round wooden table that my parents bought when they got married in the early 70s. Its fills the small room, barely leaving space to sit next to it. Around it, four wooden chairs, of a different style obviously bought at a different time than the table, and two stools, one made of wood and one made of white plastic. In the right corner, between the door leading to the kitchen and the wall are shelves piled high with old newspapers, books, and an assortment of things that may come in useful. The walls act as witness marks to when I was 13 and tried to fix the plaster and paint the house. Every time I look at them I wonder how my parents let me take on this task at such a young age and I can’t understand how they didn’t get really pissed off with the questionable results, as the walls must have looked much better before my attempts.

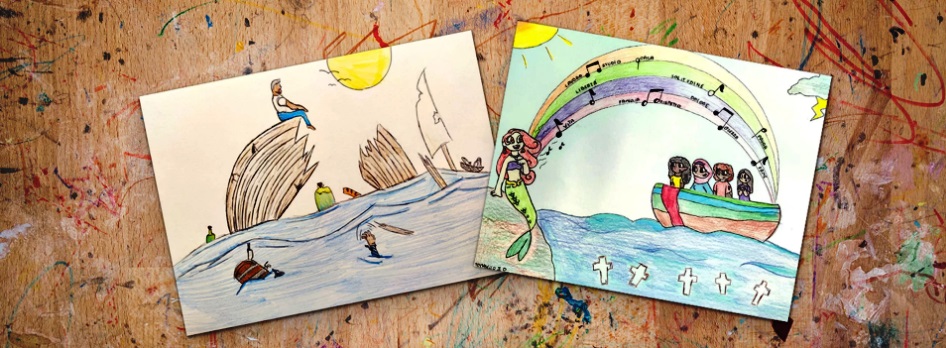

Gerda, my mother was born 23.8.1938. She made aliyah to Israel from South Africa on 12.09.1960 at the age of 21. She arrived on a boat that departed from Napoli to Haifa called The Theodore Herzl. The voyage took two or three days and on arrival, the Bnei Akiva “shaliach” and his wife took her straight from the port to see the Bahai Gardens in Haifa. She spent the following year working and studying Hebrew and Judaism on Kibbutz Yavne. She then went on to complete Judaic Studies at the Givaat Washington Teacher’s Seminar, so that she could become eligible to teach in Israel. After graduating she tried living in a few religious Kibbutzim finally ending up on Kibbutz Shluchot for two years and then moving to Jerusalem, because her friends were unsuccessful in introducing her to possible partners and had run out of options.

Alec, my father was Born 09.09.1942. when he was almost 30 years old he landed in Israel in 1972, thinking it would be a stopover on his way to Greece. He arrived via London or Paris, nobody’s quite sure. He was completely broke and needed a job and somehow found one as an English editor at the Encyclopedia Judaica Jerusalem, where he met my mother who was working there as a proofreader.

My mother’s pursuit of her Zionist dream to build a home in Israel and my father’s single child’s wish to have children somehow created a connection between these two very different personalities.

My mother is religious.

My father was secular but had a deep interest in religions.

One of the things that comes to my mind when thinking of my parents is their clothing, my mother appears wearing a light blue woolen house robe and my father has on his worn-out jeans and leather jacket.

My father inherited a small sum of money after one of his aunts died. It wasn’t much, but it was enough to buy a small 47sqm flat in Kiryat Hayovel, one of Jerusalem’s working-class neighborhoods. Before that we lived in rented apartments on Wiessberg street, in Bayit Vagan and Hameyasdim street in Beit Hakerem. We moved to our new home a few weeks before I started the second grade, my sister Bellina was in her last year of kindergarten and my brother Reuven was still running around freely at home. We were very excited about moving. Our new flat wasn’t much, it was located on the ground floor of a gray concrete, eight-story apartment block but to us it felt like a huge upgrade, because the small living room opened out to the building’s yard and we could run in and out of the house feeling the thrill of the possibilities of new adventures.

About 10 years after my father died my mother found a letter addressed to him in her mailbox. The stamp and the address on the back showed that it was sent from Zimbabwe, but the name of the sender wasn’t known to her. She didn’t open it straight away. When we arrived for Friday night dinner we found it lying on my father’s desk in the living room. At first glance, I thought my mother had received a letter from some distant family member and I asked her who it was from? She answered that it was sent to my father and that she didn’t recognize the name of the sender. We all gathered around it, I picked it up looking at it closely, hoping to retrieve some information from the envelope that my mother may have missed, but the envelope was just a normal bland airmail envelope with red and blue lines around the seams. My father’s name and address were on the front and the name and address of the unknown sender were on the back in neat handwriting. The letter changed hands between my sister Bellina, then Maya my wife and finally back to me. We all looked at it closely, but the sealed letter just lay there silently in our hands. The only thing special about it were the beautiful Zimbabwe stamps, that were exotic to our eyes and instantly claimed by my seven-year-old son Emanuel before we had a chance to even open the envelope. We all stood around it not knowing exactly what to do.

The round, out of style wristwatch that my father wore as far back as I can recall. Its once white center, that had become yellowish over time, with its plastic straps that he changed every few years attempting to keep this old piece of machinery going for a bit longer. Every afternoon he used to wind it up.

My mother’s beaten up Nikon binoculars which she has been using for about two decades. It’s a pair I got her for her birthday just when I started studying photography and decided to invest in optics. It usually lives in her clothes closet, stuffed in between her garments.

Gerda, my mother, never paid much attention to clothes or food. Both were categorized in her mind as necessities, not things that need to be relished. As a consequence, clothes were purchased when needed and food was nothing to be talked about, nourishing but for the most part tassels.

Alec, my father kept up an appearance. It wasn’t that he bought clothes. Most of the time he wore the same old Levis jeans or one of the two corduroys he owned and one of the several buttoned cotton shirts he had, possibly one of the few shirts he brought with him when he came to Israel. But even though the clothes were heavily used and mostly outdated he always looked neatly clothed.

My mother is a vegetarian and since I can remember she talked about the importance of eating healthy. My father was a meat lover and believed that we needed to eat meat every day. My mother who was constantly trying to satisfy his wishes used to cook a chicken on special occasions. I still remember how disgusted she looked when picking up the plucked bird and putting it into a pot half filled with vegetables and water. Needless to say, the result didn’t make us, or my father lick our fingers, but his wish for us to eat meat had been fulfilled.

The vegetarian/meat eating discussions ceased as a result of my father eating his main meal at work, in the Jerusalem Post’s cafeteria. But started up again when one day my father insisted on eating steak every day. This turned out to be quite the fiasco. It was the end of the 80’s and it seemed to me that every time we turned on the TV there was this ad about a new brand of frozen steak that was super easy to prepare, the slogan rhyme emphasized how soft the meat was and that it couldn’t be ruined even if it was cooked by the man in the house. Remembering the way my mother cooked the desired steak every evening, it couldn’t have been more different from the advertisement. The memory is still vivid, I can see the house full of smoke and the burnt black frying pan in which the meat was cooked till it looked like an unidentified hard gray lump that certainly was not related to the soft delicious looking steak on TV.

When Maya and I started our relationship, my father used to ask her: don’t you want a gray steak, Maya? She never knew exactly how to answer that question.

On Saturdays, me and my friends used to go from apartment to apartment following the food trail. Starting at our place at eleven o’clock in the morning with crackers and cottage cheese accompanied by freshly cut vegetables, which were conjured up by my mother as an easy solution for an early lunch. This was considered exotic by my friends who came from meateating households where crackers and cheese were not considered food and therefore did not exist. From our table, we moved swiftly to Rubi’s lunch table, where his parents and seven brothers and sisters plus other strays sat around the big Persian rice pot accompanied by Khoresh sabzi, a meat and green herbs stew or Gondi, which were big, chicken and chickpea flour balls. These dishes were always served with white bread, fresh green onions and spicy green peppers. If we were still feeling hungry after that, then we would continue on to Sammy’s house, but most often we just moved from the table to the big couch, or lay down on the carpet, watching one shitty movie after another on the illegal cable TV and going home only after it became dark outside.

My father was a hippy at heart, when he visited Israel in the 60s he had long hair and when walking with his relatives in the streets of Jerusalem his cousin asked him to walk behind them, so that nobody would think they were associated. My father never forgave him for this.

My father arrived in Israel after spending some years in Paris, London and bumming around Europe. Nobody really knows what he did there and how he survived financially, but over the years I managed to put together pieces of information. Two relatives that he was somewhat closer to say that he was 19 and in university in South Africa his father died. His father’s second wife ransacked the family house and funds leaving him penniless. Probably feeling that he had nothing keeping him in Rhodesia he traveled to Europe aspiring to become a writer. I vaguely recall him telling me that he studied law for a while at a university in London, but maybe this happened when he was younger and studying in South Africa. nobody else seems to remember this, so maybe it’s a fixation of my imagination. Leon my uncle, says he heard from aunt Aliza who was his wife, that my father had slept under a bridge for a few months in Paris. Aliza is dead now and no one else has verified this information. We all know that being broke in Paris he had slept in one of the beds on the upper floor of Shakespeare and Company, a bookshop famous for housing many aspiring young writers. But nobody knows the exact amount of time he spent there, my mother says it was for a few days, my sister remembers him saying that he stayed there for a few months. I seem to remember him saying that he stayed there for a long time, but nobody including myself seems to have really listened to his stories about this period in his life on the few occasions that he talked about his past.

My father always said to us kids: “make sure you have a roof over your heads, enough money for food and to pay the bills”. When I think of him saying this to us over the years, again and again, slowly and constantly hammering it in to his children’s subconsciousness, I believe that there must have been times in his life when he was so broke that he didn’t know when next he would eat or where he would spend the night. These rumors of him sleeping under bridges in Paris don’t seem so far-fetched.

Before my Father had children he planned to never get a real job, but to spend his time writing. In one of his books he describes a conversation I am sure I heard several times:

“What do you do?

About what?

No, I mean, what work do you do?

I don’t.

You don’t?

That’s right.

How do you spend your time?

I’m extravagant – I waste it.”

When people asked my father why he didn’t speak Hebrew he always answered:

“There’s no need I’m just a tourist in Israel, I’m not planning on staying for long”

My father always said to us, change your surname, Israel isn’t a good name to be living with, it pinpoints you as Jewish.

Lately, I asked my mother how come she doesn’t remember more about what happened in my father’s life before they met. She answered that she always thought he was exaggerating a bit, it all sounded unreal to her, and in retrospect, she hadn’t paid enough attention.

Both of my parents considered reading a worthy activity and encouraged us children to do so. From a very young age, my mother used to read us for two hours or so every night classic children’s books mainly by British writers like Enid Blyton and Arthur Ransome. She carried on doing this even when me, my sister and brother were already reading on our own. Reading has always taken up a large part of my time and the books have started piling up on shelves in our apartment, slowly a certain resemblance to my parents’ flat is taking place.

Being a single child my father wanted children and always hammered in the importance of family. He used to say: “Always remember that at the end of the day all you really have is family”. His words always echo at the back of my mind whenever I’m livid with anger at my brother or sister.

My father used a blue typewriter, he continued using it even after the first Mac came out and all the writers in the newsroom at the newspaper he wrote for had to change their working habits overnight. Eventually, he bought a second-hand Mac to work on at home. I remember we all stood around as my father turned it on for the first time and the small screen lit up with a green light. We didn’t really know what it was for, but we associated it with my father’s work. From that moment on it just sat there, collecting dust on the basic plywood desk made by one of our neighbors, a carpenter who had just immigrated here from Russia and needed work. The desk was positioned awkwardly in the living room backed up to one of the walls that were lined with shelves piled with books. It didn’t take long before the computer became another shelf to pile books on. This piece of adapted furniture stayed there for many years, it was connected to the electricity socket but as far as I remember my father hardly ever turned it on. It stayed there until my sister insisted she needed the space for the new PC she had bought when she started studying.

My father was a writer and a journalist.

My mother was educated as an English teacher but never taught officially, only the occasional private lesson for neighbor’s kids.

My mother has always been really serious about birdwatching. Her interest in birds started at a very early age. She remembers walking by a field and noticing a Wagtail and Cattle Egrets at the age of four or five. When asked what my mother did, I always said that she was a birdwatcher. Actually, that’s still the way I describe my mother today.

During my childhood, it seemed that my father was mainly at work or working at home. His life ran opposite hours to the rest of the family. He used to go to work in the evenings, leaving the apartment at the time we were showering and preparing to go to bed, returned home in the early morning. Most days, unless he was late getting home, we needed to wait for him to finish having his daily bath and go to bed. Only then could we go into the small steam filled bathroom to brush our teeth and wash our faces before having breakfast and running off to school. When we got back home he would still be asleep, or just waking up and having coffee. He used to spend the afternoons freelancing, proofreading manuscripts at home. My mother used to double check his corrections to see nothing had been overlooked.

Walking down the four stories of stairs to my mother’s apartment the ghost of me as a child dashes by me. Sometimes I’m dressed up as a cowboy or an Indian, sometimes I’m a pirate. Sometimes I have a sword or a long rifle I made out of a broomstick. Sometimes I’m alone. Sometimes accompanied by my two best childhood friends. Sometimes my mother’s voice echoes up after my fleeting ghost telling me to be back home in time for dinner. Sometimes it’s my father’s voice shouting after me to be careful.

My father liked to relax while taking long baths. He insisted on doing so even though it wasn’t really comfortable as our bathtub was tiny. It was about half the length of the standard bath size and it had a step seat in it. My mother on the other hand took very short showers, she hated wasting water.

Typical questions my father used to ask my mother:

… Gerda, what is this book you are reading?

… Gerda, this looks like something that the cat brought in…

Alec: Gerda, the cat is in the house

Gerda: no response

Alec: GERDA, THE CAT IS IN THE HOUSE

Gerda: no response

Alec: GERDA, Le Chat est dans la Maison

Gerda: no response

On my first day at photography school, I was asked to make one photo that condensed within it the meaning of home. I shot a whole roll of slide film in and around my parents’ apartment and after developing it I chose a vertical image of my father sitting on the rocking chair illuminated by the yellowish orange light from the tungsten light bulb in the orange plastic light shade hanging from the ceiling in the center of the living room. In the background were the wooden framed windows, a reproduction of a Japanese painting and the edge of the library that covered most of the wall from ceiling to floor. I think I subconsciously chose this image because the living room was very much my father’s room, and the image of him sitting in it echoed a recurring image embedded in my mind. Lately, I have tried to locate that image unsuccessfully. I can still remember every detail of it despite the fact that I haven’t seen it since I projected it on the class wall in 1997 and I still look for it in my archive and in my parents’ house hoping to stumble upon it. Since that day I started photographing my parents and our home, I carried on photographing for about three years. The work slowly started to accumulate in the plastic binder that became its home. After my father died I stopped photographing and couldn’t bring myself to look at the images for ten years. They lay there, sealed in the negative plastic binder waiting. They reminded me too much of my fathers’ death. At a certain point I took them out of the cupboard and moved them to the table of my guest room/storage room/home studio where they rested untouched for a few months longer. One night I drew up enough courage to look at them again on the small lightbox. I placed the transparent plastic storage pages one after the other against the white light looking at the negatives and slides in a variety of formats. I found myself remembering many of the moments in which the images were taken. I think that was the moment I decided that I should carry on photographing at home despite the emptiness that took over the apartment after my father died.

Photographing my father and mother became a small ritual. It always felt like they were trying to humor me and that they wanted me to get on with it and let them go back to whatever they had been doing. My father’s usual complaint after standing or sitting in the same spot for long periods of time, while I operated the large format 4×5 inch camera was: “You do know that they have invented cameras that all you need to do is press a button, I really don’t understand why you insist on using such an old thing”. My mother used to participate more patiently, she hardly said a word, occasionally asking if I had finished.

Judging by the many writer’s manuals and guides that we had at home, I assume my father was frustrated that his books never got published by big publishing houses, but I can’t remember him ever saying anything about it. My mother always seemed content with the hand life dealt her.

My father and mother used to talk to us in English. My mother occasionally used to switch to Hebrew. Us kids used to mix the two and in the family, we used to call this new lingo ‘Pinglish’.

I remember one day my father didn’t go to work. He woke up but didn’t feel well and stayed in bed. The next day the same. His legs started to swell and he called the family doctor who came and gave him a shot, but didn’t really know what was wrong. After another day or so we finally took him to the hospital. The doctors found that he was suffering from kidney malfunction. I’m sure that he already knew this from day one. This disease that runs in our family and now I turns out that I have too. He didn’t want to think about it and preferred to believe that everything would be all right.

I was cleaning up the sticky mess left on the bar from the previous night, clearing away the dirty glasses and filling up the refrigerators with bottles of soft drinks and beer at the bar where I was working when the phone near the cashier rang. It was early evening of Hoshana Raba, the second festive day of Sukkot, I think it may have been celebrated that year on a Friday night but I’m not sure. On the other side of the receiver was my mother who informed me in a trembling voice that she was in the toilet when she heard something heavy falling. She called out to my father, but he didn’t answer, so she quickly came out and found him on the floor. She called the ambulance and now she was calling me. I ran to the restaurant’s kitchen shouted over the counter to the boss that something had happened, and I dashed out.

Cleaning out the flat at Brazil street 28/26. So many of my memories are located between these apartments walls and its surroundings. Endless family meals, discussions, arguments and fights and naturally also a few good memories associated with the endless times spent together and alone within this 47sqm. Memories of childhood and family. Memories of my mother and father. Now the place has been emptied of the hundreds of books that lined the walls and tables. Now that we throw away all my father’s clothes that have been hanging in the cupboard accumulating dust for more than a decade in which we couldn’t bring ourselves to throw them away as if they still held something of him in some way. Now that we have given away, sold or recycled all the books and piles of old newspapers that meant so much to my father, who had collected them for specific purposes that meant nothing to anyone else. Now that we convinced my mother to agree to throw away all the old broken pots and the blackened frying pans she has been using since the 70s. Now that we have disassembled the cheap broken cupboards and thrown them away. Giving the place a last look around, the place feels strange, as if we recycled or threw away all our family memories when we stripped the apartment from all the junk we had accumulated over the decades. It seems the place has been emptied of all memories, the walls have let go of the previous inhabitants. I can nearly hear them breathe in relief as if to shake off a burden, preparing itself for a new family.

This text is dedicated to my son Emanuel with the hope he will remember his parents’ eccentricities with fondness.